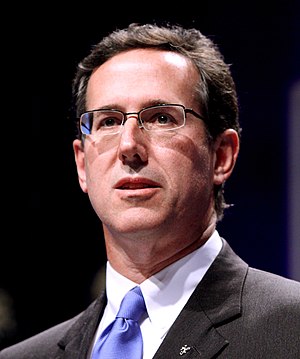

Former Pennsylvania U.S. Senator Rick Santorum has now become the darling of the GOP right-wing evangelical "values" voters. Santorum claims that his worldview has been shaped by his commitment as a Catholic to his church's social teaching. But is that true?

Santorurm's professed "Catholic worldview" has led him to assert that President Obama is waging war against the Catholic Church by requiring its institutions to provide for contraceptive care for their employees as part of their health insurance; he has railed against abortion, supported capital punishment, supported "right to work laws," and opposed government regulation of the economy and any and all efforts to regulate the possession and display of fire arms.

In addition, he has vociferously denied the existence of climate change and criticized President Obama's commitment to the environment and his efforts to support the development of alternative sources of energy as a "phony theology" that endorses an "Earth-based" conservation mentality. Simultaneously, Santorum has embraced a bellicose foreign policy that supports the current Israeli Likud Party's hard-liners, recommended war if necessary against Iran and questioned whether continued U.S. involvement in the United Nations and other international agencies is a a surrender of the country's sovereignty.

Santorum's website touts his commitment to limited government, fiscal conservatism and family values: "Every American should have access to high-quality, affordable health care, with health care decisions made by patients and their physicians, NOT government bureaucrats America needs targeted, market-driven, patient-centered solutions to address the costs and underlying causes of being uninsured rather than a one-size fits-all, government-run health care system."

"Rick Santorum is committed to reviving our economy, restoring economic growth, and creating jobs in America again by unleashing innovation and entrepreneurship through lower and simpler taxes for American businesses, workers, and families. He also will roll back job killing regulations, restrain our spending by living within our means, and unleash our domestic manufacturing and energy potential. His vision for America is to restore America's greatness through promotion of freedom and opportunity for all. This is just the start. A plan made in America to promote America's families and prosper its businesses."

"Coming from Pennsylvania, a state with a rich heritage of hunting and fishing, Senator Santorum understands firsthand the importance of preserving our constitutionally protected rights found in the 2nd Amendment. Senator Santorum fights to preserve this tradition, and will work to ensure these rights are not infringed upon."As a Senator, Rick Santorum opposed frivolous lawsuits against the gun industry by supporting legislation (The Protection of Lawful Commerce Act) that would protect law abiding firearms manufacturers and dealers from frivolous lawsuits attempting to hold them liable for criminal acts of third parties."

Santorum's website further proclaims that, "As a believer in American Exceptionalism.... Rick Santorum understands that those who wish to destroy America do so because they hate everything we are - a land of freedom, a land of prosperity, a land of equality....As an elected representative, Rick knew that his greatest responsibility was to protect the freedoms we enjoy - and we should not apologize for holding true to these principles."

The question that now needs to be answered, however, is whether the allegedly "conservative values" that Rick Santorum professes to endorse are consonant with the tradition of Catholic social philosophy and whether they are, in fact, conservative at all? All of the evidence suggests that they are not.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has issued a guide entitled Sharing Catholic Social Teaching: Challenges and Directions. It emphasizes that "The Catholic tradition teaches that human dignity can be protected and a healthy community can be achieved only if human rights are protected and responsibilities are met. Therefore, every person has a fundamental right to life and a right to those things required for human decency. Corresponding to these rights are duties and responsibilities--to one another, to our families, and to the larger society." As such, "Human dignity can be protected and a healthy community can be achieved only if human rights are protected and responsibilities are met. Every person has a fundamental right to life and a right to those things required for human decency - starting with food, shelter and clothing, employment, health care, and education. Corresponding to these rights are duties and responsibilities -- to one another, to our families, and to the larger society."

Under a section entitled "Option for the Poor and Vulnerable," the guide proclaims: "A basic moral test is how our most vulnerable members are faring. In a society marred by deepening divisions between rich and poor, our tradition recalls the story of the Last Judgment (Mt 25:31-46) and instructs us to put the needs of the poor and vulnerable first." Indeed, this option is a major barometer of one's commitment to social justice since "The moral test of a society is how it treats its most vulnerable members. The poor have the most urgent moral claim on the conscience of the nation. We are called to look at public policy decisions in terms of how they affect the poor. The 'option for the poor,' is not an adversarial slogan that pits one group or class against another. Rather it states that the deprivation and powerlessness of the poor wounds the whole community. The option for the poor is an essential part of society's effort to achieve the common good. A healthy community can be achieved only if its members give special attention to those with special needs, to those who are poor and on the margins of society."

Equally emphatic is the Catholic Church's rejection of those economic doctrines that have elevated the primacy of the markets and capitalism over basic human needs. "The economy must serve people, not the other way around. All workers have a right to productive work, to decent and fair wages, and to safe working conditions. They also have a fundamental right to organize and join unions. People have a right to economic initiative and private property, but these rights have limits. No one is allowed to amass excessive wealth when others lack the basic necessities of life." Although "Catholic teaching opposes collectivist and statist economic approaches.... it also rejects the notion that a free market automatically produces justice. Distributive justice, for example, cannot be achieved by relying entirely on free market forces. Competition and free markets are useful elements of economic systems. However, markets must be kept within limits, because there are many needs and goods that cannot be satisfied by the market system. It is the task of the state and of all society to intervene and ensure that these needs are met."

The section styled "The Dignity of Work and the Rights of Workers," expresses the Catholic Church's long-standing endorsement of unions and the need for government regulation of the economy in the public interest: "The economy must serve people, not the other way around. Work is more than a way to make a living; it is a form of continuing participation in Gods creation. If the dignity of work is to be protected, then the basic rights of workers must be respected--the right to productive work, to decent and fair wages, to the organization and joining of unions, to private property, and to economic initiative." Consistent with this view, "All people have a right to participate in the economic, political, and cultural life of society. It is a fundamental demand of justice and a requirement for human dignity that all people be assured a minimum level of participation in the community. It is wrong for a person or a group to be excluded unfairly or to be unable to participate in society."

The Catholic Church's positions on war and the environment are equally unambiguous. They are rooted in a broad vision of the obligations that we as human beings owe to one another and as stewards of the earth: "We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences. We are our brothers and sisters keepers, wherever they may be. Loving our neighbor has global dimensions in a shrinking world. At the core of the virtue of solidarity is the pursuit of justice and peace. Pope Paul VI taught that if you want peace, work for justice. The Gospel calls us to be peacemakers. Our love for all our sisters and brothers demands that we promote peace in a world surrounded by violence and conflict." Further, "We show our respect for the Creator by our stewardship of creation. Care for the earth is not just an Earth Day slogan, it is a requirement of our faith. We are called to protect people and the planet, living our faith in relationship with all of Gods creation. This environmental challenge has fundamental moral and ethical dimensions that cannot be ignored."

The kind of anti-government rhetoric advanced by Senator Santorum and the other professed Catholic GOP Presidential contender, Newt Gingrich, are at loggerheads with the Catholic moral teaching that is an essential part of the conservative political tradition.Because it traces its lineage from Aristotle, through Thomas Aquinas, to Catholic philosophers today, that authentically conservative tradition is fundamentally at odds with the kind of anti-social individualism that dominates current GOP political discourse. In stark contrast to Catholic social teaching, that discourse draws its values from the tradition of classical liberalism that emerged after the Protestant Reformation and was trumpeted by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, David Hume and Adam Smith, among other English thinkers.

Catholic social doctrine insists upon the importance of government as a positive instrument to advance the public good. For that reason, the current assault that is being waged by Santorum and his Republican supporters upon government is impossible to square with historic Catholic social teaching. As the guide, Sharing Catholic Social Teaching: Challenges and Directions. Guide to Catholic Social Teaching explains, "The state has a positive moral function. It is an instrument to promote human dignity, protect human rights, and build the common good. All people have a right and a responsibility to participate in political institutions so that government can achieve its proper goals. The principle of subsidiarity holds that the functions of government should be performed at the lowest level possible, as long as they can be performed adequately. When the needs in question cannot adequately be met at the lower level, then it is not only necessary, but imperative that higher levels of government intervene..."

In his encyclical, Mater et Magister, Pope John XXIII emphasized the central role of the state in promoting social justice: "As for the State, its whole raison d'etre is the realization of the common good in the temporal order. It cannot, therefore, hold aloof from economic matters. On the contrary, it must do all in its power to promote the production of a sufficient supply of material goods, 'the use of which is necessary for the practice of virtue.' It has also the duty to protect the rights of all its people, and particularly of its weaker members, the workers, women and children. It can never be right for the State to shirk its obligation of working actively for the betterment of the condition of the workingman. "

Rick Santorum has expressed no commitment to the idea of social justice, nor does he understand that the notion that the public interest is something different and distinct from a mere aggregation of self-interests. He also denies that the role of government, to use the words of A.D. Lindsey, is to "hinder the hindrances" - that is, to eliminate those impediments that stand in the way of a person's moral and civic development. For those reasons, Santorum may be a Catholic in his theology, but his social philosophy and his politics are decidedly anti-Catholic.